In the quest to design algorithms for real-time generative art, there are some dangers to avoid. One of the biggest dangers is what is known as the complexity class.

Complexity class is a classification of the runtime requirements of space and time of a particular algorithm. The classification uses the Big-O notation, and is meant to describe if the algorithm scales well or not.

As an example, with this notation, O(1) means an infinitely scalable algorithm, and O(n!) means you should abandon all hope that your computer will ever have enough power to compute your algorithm ever. So, we should really try to avoid the later...

Cellular automata have O(n) complexity, which is not too bad. They get this because they are based on a grid and the transition rule (which is calculated with the local neighbours) don't depend on the size of the grid. Here the 'N' is the size of the grid.

There are other algorithms which seem on the surface very similar but reveal themselves to be monsters in disguise. Take the Boids algorithm, for example. It is a well known algorithm invented by Craig Reynolds that simulate birds flocking, with simple rules and that shows remarkable emergence patterns.

Here, 'N' is the number of birds. The algorithm, like cellular automata, is also based on local rules and the next state of each bird depends also on it's local neighbours, but to calculate each bird state we have to go through all the other birds to select its neighbours, which makes the algorithm O(N^2), which is really bad...

Cellular automata model the world as fields while Boids model the world as particles. This distinction appears very often in simulations, like fluid flow, where it is called Eulerian (fields) and Lagrangian (particles). Of course that not all particle algorithms have O(n^2) complexity but sometimes a design choice can have a big impact on the performance of the algorithm.

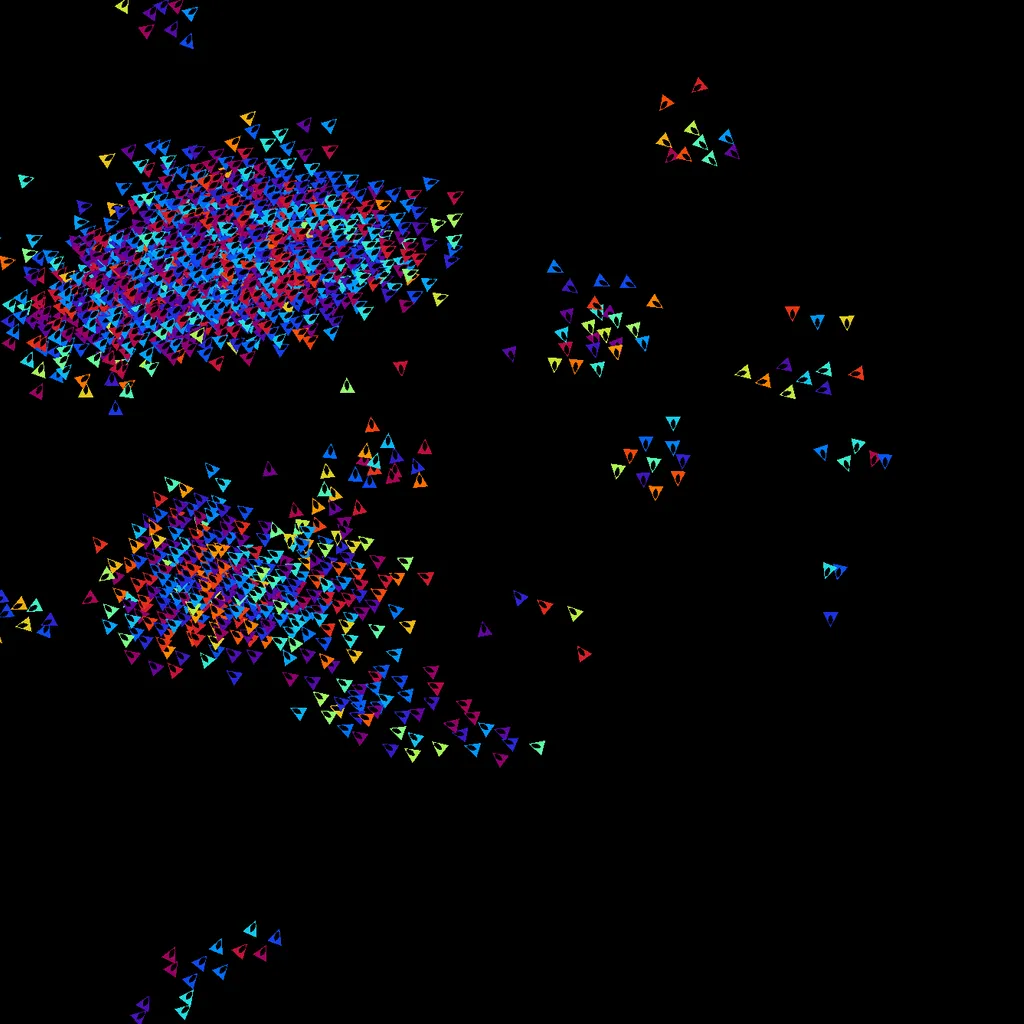

Here is an implementation of the Boids algorithm on the GPU. They try to synchronize their movement and velocity but also their blinking phase with their neighbours. The algorithm works a little bit like heat dissipation, where they try to average out their properties with their neighbours and values tend to converge overtime, but instead of maximum entropy, a global coordination emerges and they create flocking and blinking patterns.